There aren’t many competition cars that can claim to be as iconic as the Porsche 917—but it wasn’t just the car’s wide, purposeful stance, low lines, and howling flat-12 that made the model so memorable. Its legend is forever tied to its dominance on track, and the huge success it had in the top-flight of international endurance racing—particularly at Le Mans—between 1969 and 1971. Inextricably linked to the biggest names and most striking liveries in racing, its mythos was only reinforced by its appearance in Steve McQueen’s Le Mans.

Like a virtuoso young singer struck down in their prime, the Porsche 917 left only glowing, sepia-tinted highlights when it was regulated out of the International Championship for Makes. It raced on for a short while in Can-Am competition, but its competition career was nonetheless short and sweet, winning everything and cementing a lasting legacy.

Some sportsmen are so gifted that their presence alone forces a change in the rules, and after a regulatory tweak that effectively banned the Porsche 917, it seemed unlikely that the model would ever race at La Sarthe beyond 1971. That all changed less than a decade later, just prior to the introduction of Group C in 1982. In order to give manufacturers time to develop their cars and technologies, the existing Group 6 rules were relaxed, temporarily re-opening the door to one of the most dominant sports racing cars of a generation: the Porsche 917.

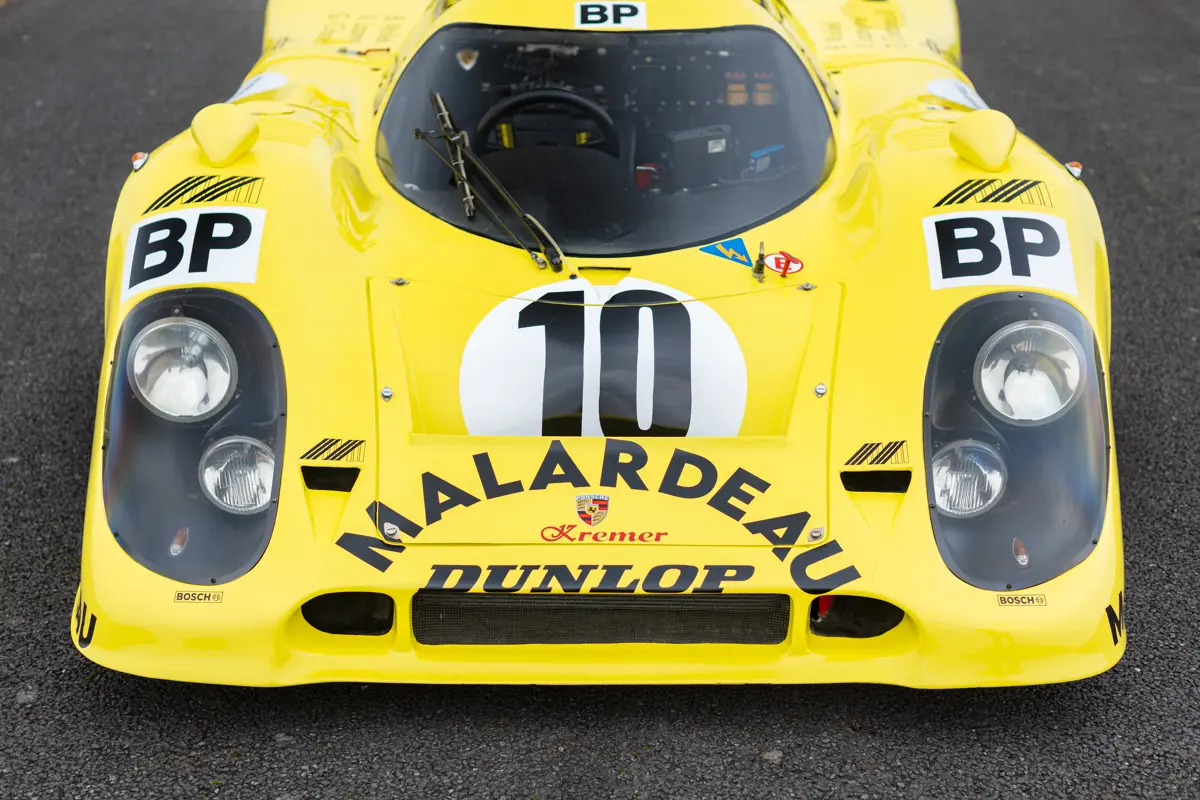

The Kremer brothers were the first to realise the opportunity. The Köln-based Kremer Racing team had good form at Le Mans and plenty of recent history with Porsche, having won the race outright in 1979 with a 935 K3—the first time a rear-engined car had won the French epic—and Stuttgart was warm to the idea of the 917 making a comeback. The factory supplied the brothers with original chassis schematics, in addition to building the team two brand-new Type 912 engines in 4.5- and 5-litre guise. The team set about their work quickly, building up a brand-new car based on a reinforced aluminium space frame chassis packed with additional bracing: technology had moved on in leaps and bounds in the intervening years, and the additional forces exerted even by stickier tyre compounds had to be taken into account. Aerodynamic understanding had also advanced, so the new car was fitted with uprated bodywork that included new side skirts to take advantage of ground effect, and an enormous full-width rear wing to keep the driven wheels planted. Brakes and suspension components, meanwhile, picked up from where development had stopped at the end of the model’s Can-Am career. The new car was even fitted with air jacks.

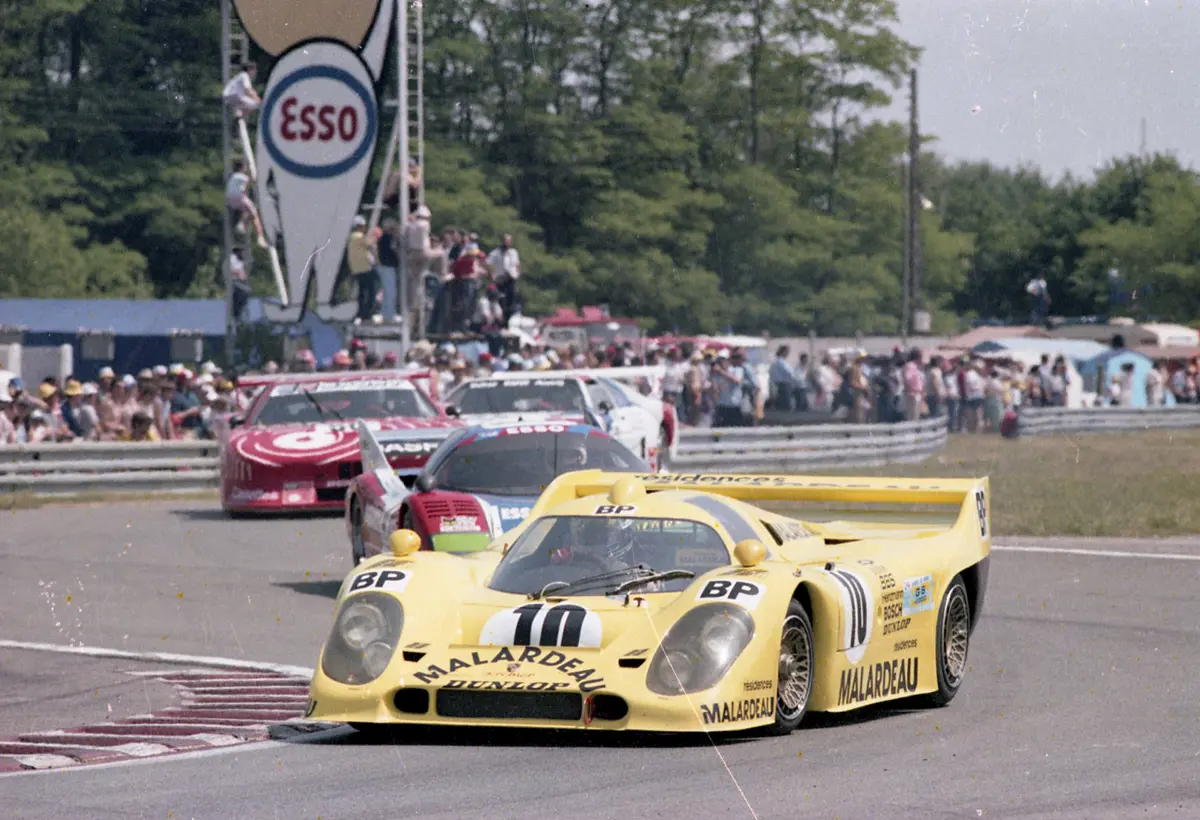

Time wasn’t on the team’s side, and the finishing touches to the car were made just weeks before its maiden outing at the 1981 24 Hours of Le Mans. The man charged with driving the car on its debut was Bob Wollek, the hero who had taken the overall win at La Sarthe two years earlier, but the initial practice sessions met with disappointing results. The car was much slower than expected, likely due to the aerodynamic additions that hadn’t been fully tested in the wind tunnel, and it qualified just 18th, lagging even its 935-K3 stablemate.

A change in gear ratios mitigated the problem, but the top speed needed to exploit the flat-out Mulsanne Straight—and to put the car into overall contention—never fully materialised. Despite the flat performance, Wollek managed to hustle the Porsche into the top 10, but neither Xavier Lapeyre nor Guy Chasseuil could maintain the position and, as the race wore on, the team fell to 20th place. The car dropped further behind when Chasseuil ran the car dry, and after seven hours of racing Lapeyre clipped a kerb and damaged an oil line, finally putting an end to one of the most daring expeditions the Circuit de la Sarthe had seen in decades.

The Porsche 917-K81’s famous Le Mans outing would remain one of the great ‘What if?’ stories in motorsport. Had the team left enough time to properly test the car in a wind tunnel, it is very possible that they would have found the speed required to challenge for honours. As if to rub salt in the wounds, the car’s only other competitive outing, at the Brands Hatch 1000km, only underlined the Porsche’s potential. The 917-K81 was ideally suited to the short circuit, qualifying just 1.5 seconds off the leader and running in 2nd place when a suspension failure forced its retirement. Incredibly, it had lapped the Kent circuit more than two seconds faster than the quickest 917 time set by Denny Hulme and Vic Elford in 1970.

Following its all too brief return to frontline racing, this incredible car kept a low profile, first with the Kremers and later a prominent Porsche collector. Owned by its current caretaker since 2011, it has only returned to the track for the occasional track day. But with its 5-litre engine having recently been rebuilt by model specialist Crubilé Sport—and reportedly putting out significantly more power than factory cars of the period—the possibilities for the 917-K81’s redemption are limitless. We can’t think of a more fitting entry for the next Le Mans Classic and can only imagine the feeling of crossing the finish line having helped this significant racer finally reach its full potential.