In today’s motor racing parlance, the gentleman racer is a key part of any supercar manufacturer’s target demographic. From Maserati to McLaren, the concept of private individuals mixing it on track from non-professional backgrounds is a big money-spinner.

However, most of these activities are, pretty much, arrive-and-drive affairs—fly in for qualifying, hopefully fly out covered in champagne and glory on the Sunday. The awkward part—the logistics, the preparation, the fixing things, the running—is taken care of by the manufacturer.

For Rob Walker, perhaps the ultimate gentleman racing driver and team owner, his lot was to take in all of these facets and, if it wasn’t for a promise to his new wife in 1940 not to continue behind the wheel, he could have become one of the pre-eminent drivers of the post-war era. Instead, he chose to become a team owner, and in doing so became the first private entrant to win a Formula 1 Grand Prix, plus many more successes.

We’re getting ahead of ourselves, however.

Rob Walker was the heir to the Johnnie Walker whisky empire, born in 1917. At the age of seven, he saw his first race at Boulogne-sur-Mer, sparking off a lifelong love of the automobile. He got his first four years later—by the age of 21 he had a fleet of 21 cars.

It was that year that Rob met the two major loves of his life—his wife, Elizabeth (Betty) Duncan, and the Delahaye 135 S Works that will be auctioned in London on 1-2 November. He acquired the Delahaye via hire purchase after spying it in a Park Lane showroom—at the time his monthly stipend wouldn’t quite stretch to purchasing the car in one go; after all, he was a student at the time.

The car already had a storied life—one of two works 135 Ss built, Albert Divo took it to 4th at the Trois Heures de Marseille, 12th at the Grand Prix de l’A.C.F., then 6th at the Grand Prix de la Marne in Reims. It was then imported to the UK via Count Heyden and sold to Tommy Clark, who raced it in the 1936 RAC Tourist Trophy and the Donington Grand Prix before selling to the Siamese Prince Chula for his White Mouse Stable, to be driven by his cousin, Prince Bira.

Bira then raced the car at Pau and Donington in 1937, before heading to Brooklands for the BRDC 500 Kilometre race, where he took 7th overall. It was then sold back to Heyden, who loaned it to several racers throughout the 1938 season.

Walker continued Delahaye's competition career immediately—you can read more about this fabulous car here.

However, once Walker had competed with it at Le Mans, where he finished 8th overall having driven for more than 16 hours—powered by a reviving glass of champagne and a change from pin-stripe suit to Prince-of-Wales check for the morning stint—thoughts turned to marriage.

Betty’s ultimatum was that he had to give up driving, and he duly hung up his racing overalls.

After serving as a pilot with the Fleet Air Arm during WW2, seeing action in the Mediterranean and the Far East, he moved into team management. Shortly after purchasing Pippbrook Garage in Dorking in 1947, he formed the Rob Walker Racing Team.

He first set up with Guy Jason-Henry on driving duties, who teamed up with Tony Rolt for the 1949 Le Mans 24 Hours in the Delahaye. It would be the start of a near three-decade motorsport adventure that would take in single seaters, endurance racing and Formula One, with some of the biggest names in motorsport getting behind the wheel.

The path wasn’t always easy. Jason-Henry was responsible for having the Delahaye’s fuel tanks stuffed with thousands of Swiss watches, which saw the car impounded on its return to the UK. Having turned Queen’s Evidence he was later acquitted but, to Walker’s dismay, he was charged £300 for the release of the car. Indignant, Walker wrote a letter to The Times asking if Cunard Line had to buy back the Queen Mary every time a passenger was caught smuggling a pair of nylon stockings. It was this dry wit that led to Walker becoming a popular contributor to the likes of Motor Sport, Road & Track, and many more.

Rob sold the Delahaye in 1949 and bought a brace of Delage single-seaters in 1950, but the first proper success came with a switch to Connaughts in 1953. Tony Rolt scored 3rd place at the Lavant Cup for F2 cars, and Eric Thompson took victory next time out at Snetterton. By season’s end, the team had picked up eight wins in club racing, and impressed on the international stage at the Rouen Grand Prix for F1 and F2 cars, with Stirling Moss taking 4th place in a Cooper-Alta.

After a few more years in club racing, which yielded only retirements in the international races the team took part in, Walker turned his hand to international racing full-time in 1958 with Maurice Trintignant driving full-time, and Stirling Moss and Tony Brooks joining in when not driving for Vanwall. It would be a promising year, with Moss and Trintignant taking the first wins for a Cooper chassis with victories at Argentina and Monaco. The win for Moss was even more special when you consider that he did the entire race on one set of tyres—it was the first privateer win in F1, and the first post-war win for a rear-engined car.

Moss would finish 3rd in 1959, taking victories in Portugal and Italy, but an early retirement in the season-ending US race destroyed his title aspirations. He would win at Monaco in 1960 and 1961 on the way to 3rd in the championship both years. The 1961 win was notable for it being the first Lotus F1 victory, and the season of firsts didn’t stop there. Moss took Walker’s Ferguson P99 Climax to victory at the Oulton Park Gold Cup, claiming the first four-wheel-drive car to win an F1 race.

However, the dream was starting to go sour—not only was form dipping, but Stirling Moss was seriously injured at Goodwood, and Ricardo Rodriguez and Gary Hocking both died during the 1962 season. Walker’s garage was also taking off, providing servicing and, later, Ford sales.

It had been a glorious period with Moss—Walker and the British driver won half of the 100 races they entered in F1, F2, Intercontinental Formula, Tasman, and GT races, including two RAC Tourist Trophy victories back-to-back at Goodwood. However, he would never return after his crash at the Chichester circuit, and though Walker considered closing down the team, he entered the 1963 season with Jo Bonnier, and Jo Siffert buoyed the team from 1964 onwards.

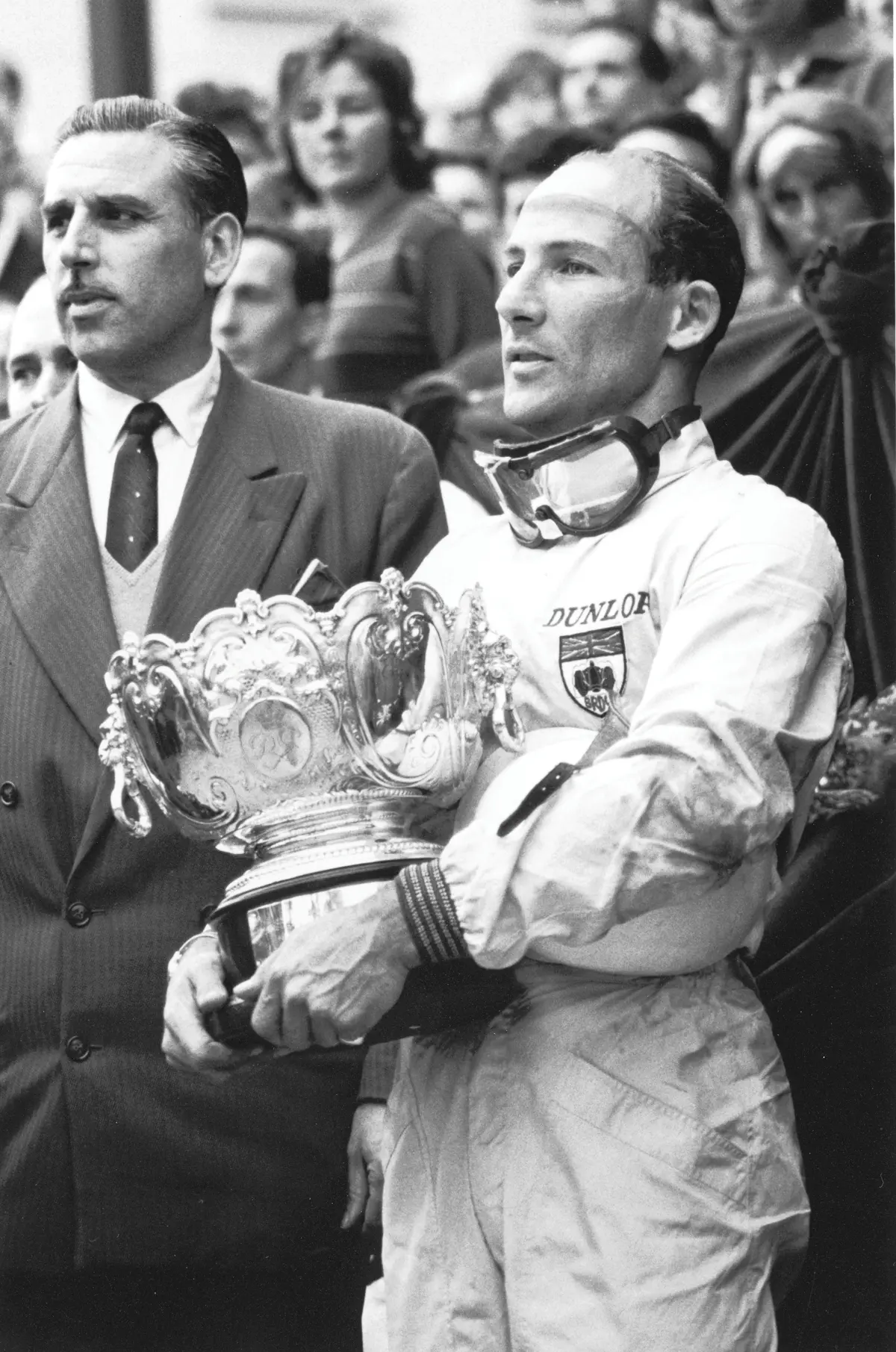

Success would be fleeting, however. Other than 3rd place at the US GP in 1964, it would take until the arrival of a Lotus 49B for Walker’s team to stand atop the podium. Siffert won a race of attrition to take the team’s final win at the 1968 British Grand Prix. Again, it would be a bittersweet year—earlier in the season the Pippbrook Garage had been ravaged by fire, destroying much of the team’s equipment and two cars. It’s understandable that Walker deemed the Silverstone win the sweetest of all, considering the year he’d had.

By this point, privateers were starting to be eased out as costs, driver contracts, and the scramble for sponsorship took hold. Brooke Bond Oxo stepped in to replace London stockbroker Jack Durlacher on the sponsorship front in 1970, which set up a year running Graham Hill with little success. In 1971 he merged the team with John Surtees, taking the sponsorship with him—and the Pippbrook Garage was dedicated to Walker’s classic cars.

One of which was an old friend—the very Delahaye that he drove at Le Mans in 1939. Bought unseen at a Sotheby’s auction in 1970 for £5,000, it was in a dilapidated state. Walker entrusted it to John Chisman to fabricate a new body, copying the scale model of the car that had been created for Walker by Henri Baigent. The process took eight months, and in 1973 Walker returned the car to the Circuit de La Sarthe for a 50th Anniversary historic sportscar support event for the 24 Hours race, where it was driven by Stirling Moss.

The Rob Walker Racing Team would formally come to an end in 1975 after running Alan Jones in a Hesketh, and Walker devoted his attention to managing Mike Hailwood and developing his own journalism career. He still produced reports for Road & Track long into the 1990s.

For British audiences, some of his most entertaining writing could be found in Motor Sport magazine, telling readers some of the ups and downs of not just running a racing team, but some of the finest road cars of the day. At the recent Chantilly Arts & Elegance concours, his alloy-bodied Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing won the SL class. The first 300 SL delivered to a private owner in the UK, beating Aston Martin’s David Brown by a week, it was first delivered in a very bright red in alloy body form. His travails driving what would have been a controversial German car on UK roads make for entertaining reading, particularly after his wife found herself coming over all queasy washing the bright red paint—it would end up being painted white. It’s certainly worth a read – and you can find it here.

Rob Walker passed away in 2002 at the age of 84. He was a rare one-off, who took the fight to the big guys as a privateer in Formula 1—and won. It’s likely that such a feat will never be seen again. We are also unlikely to see his like again, for there are many gentlemen drivers, but we imagine very few have the title listed on their passport, as Rob Walker did.

To see the full Rob Walker Collection of trophies, art, and memorabilia—plus the Delahaye—head here.