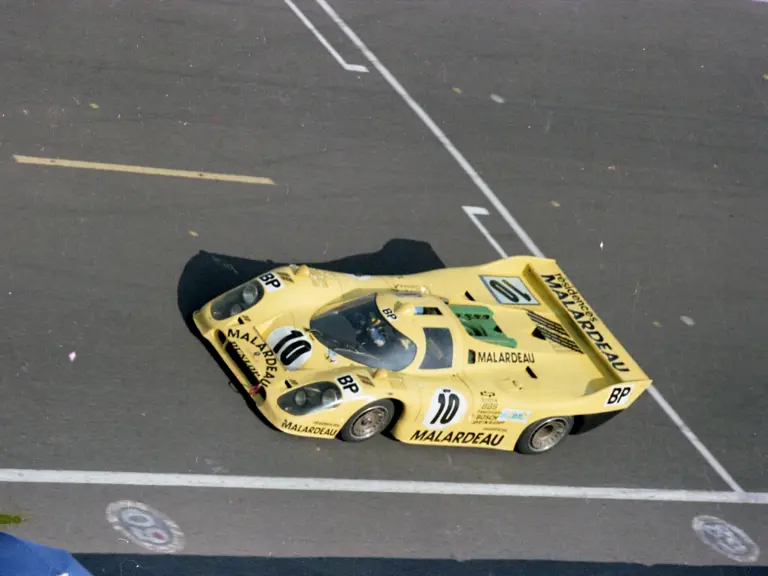

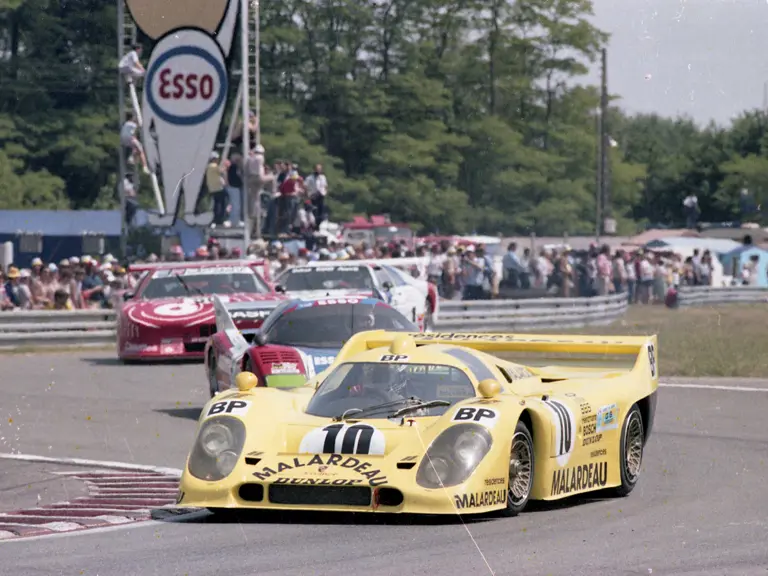

1981 Porsche 917 K-81

{{lr.item.text}}

€2,648,750 EUR | Sold

{{bidding.lot.reserveStatusFormatted}}

- Constructed by Le Mans-winning team Kremer Racing with full co-operation from Porsche AG

- The final factory-blessed 917 built, and the last of the model to compete at the 24 Hours of Le Mans

- Raced in the 1981 edition of the race; driven by Bob Wollek, Xavier Lapeyre, and Guy Chasseuil

- Contested and led its second—and final—race at the 1981 Brands Hatch 1000 Kilometres, driven by Wollek and multiple Le Mans winner, Henri Pescarolo

- Benefitting from an engine rebuild in 2019 with very limited use since

- Highly eligible for many historic racing events

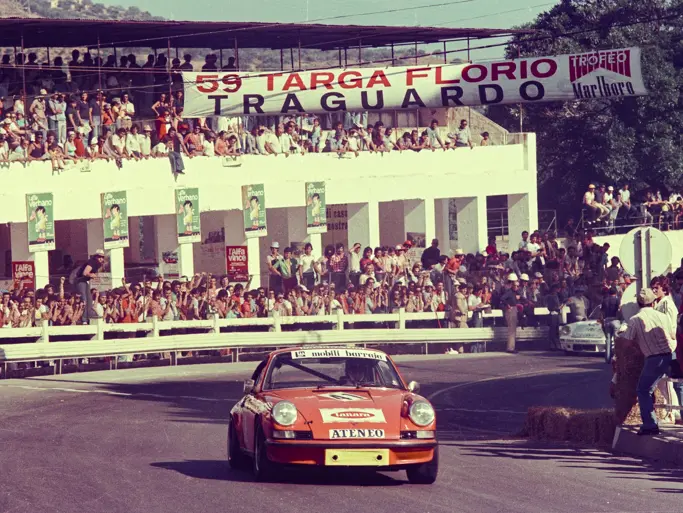

In contrast to other era-defining designs such as the Alfa Romeo 8C, Jaguar D-Type or Porsche 956/962, the 917’s racing career in its original coupé form was only fleeting. It involved less than three seasons and a mere 23 World Championship events. Remarkably, the car emerged victorious in 15, including wins at both Daytona and Le Mans in 1970 and again in 1971.

Rendered ineligible for international racing in 1972, the 917’s legacy was further secured by two dominant seasons in the unrestricted North American Can-Am Championship, in which the Penske Racing team’s 917/10 and 917/30 Spyders secured consecutive titles in 1972 and 1973, respectively. Nevertheless, the introduction of new fuel restrictions for 1974 heralded Porsche’s withdrawal from the series, and after barely five seasons of top-flight competition, it appeared that the chapter had closed on arguably the most charismatic—and certainly the most coveted—of all Porsches.

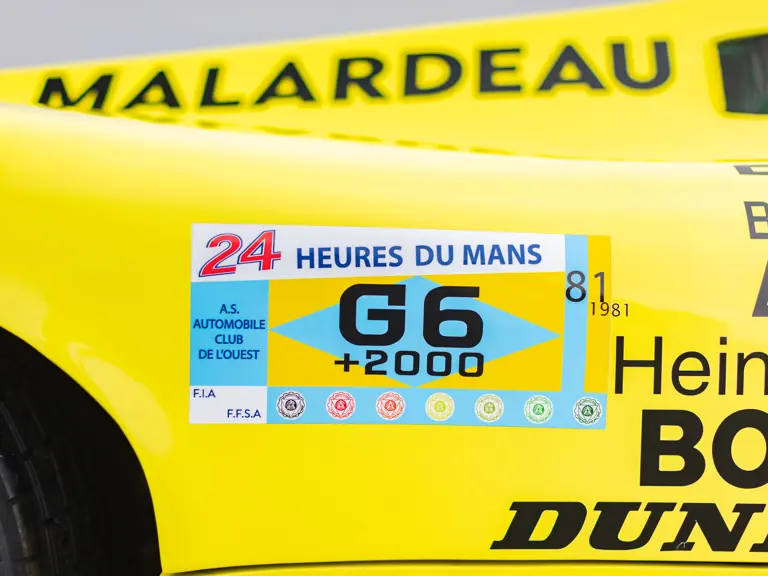

However, some 12 years later, the Porsche 917 would return for a belated competitive swansong. Indeed, as the FIA sought to transition to the new-for-1982 Group C ruleset, the existing Group 6 regulations were relaxed for the 1981 World Endurance Championship season to stimulate development of both new components and cars for the incoming formula. Buoyed by an unlikely victory at Le Mans in 1979 with their self-developed Porsche 935-K3, the Köln-based Kremer team sought to exploit such technical latitude by developing its own updated Group 6 version of the 917. It was a car that offered the team realistic chance of a second victory at La Sarthe in three years.

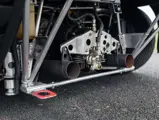

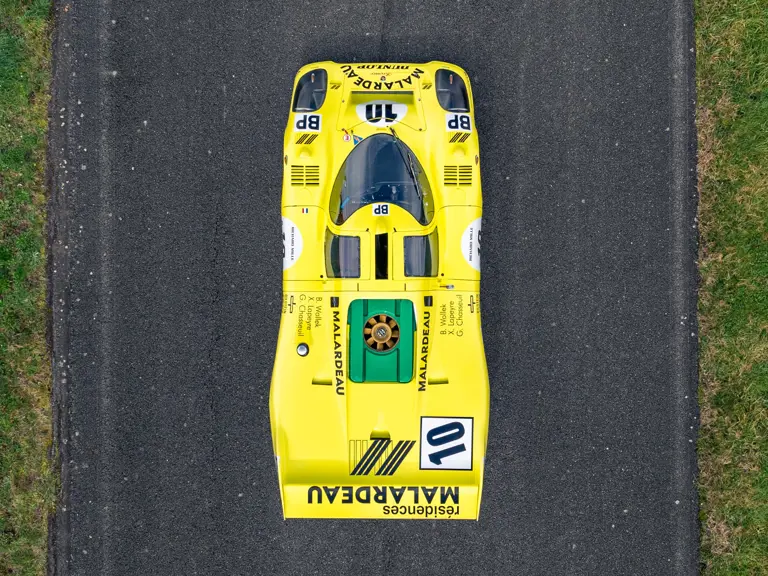

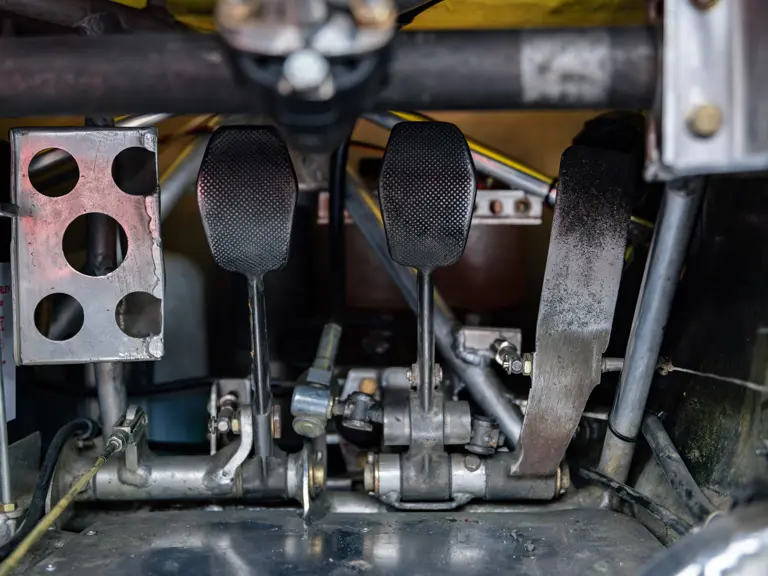

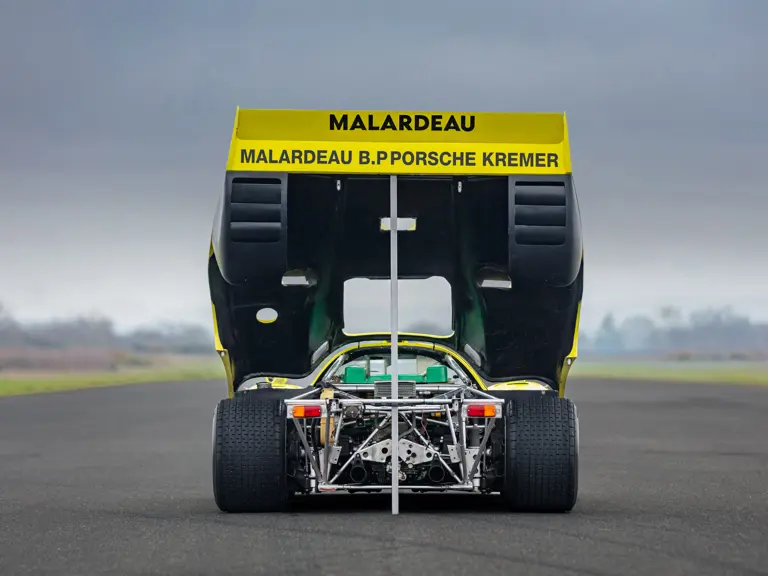

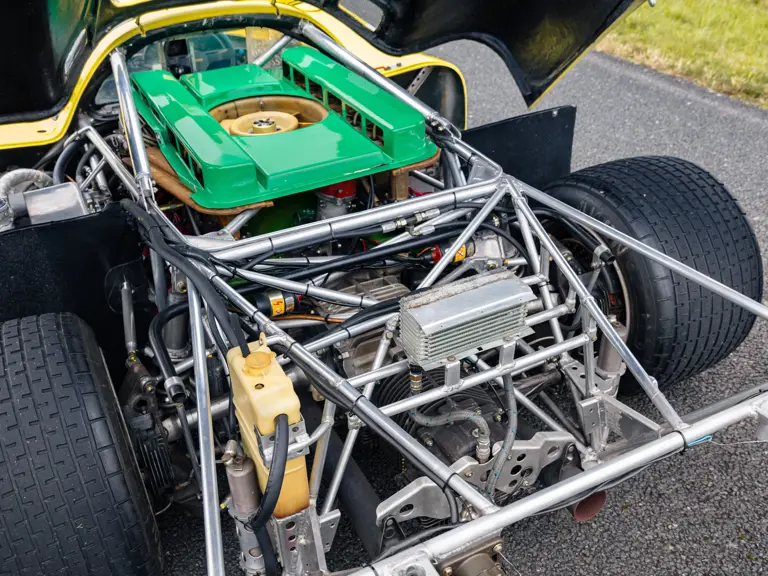

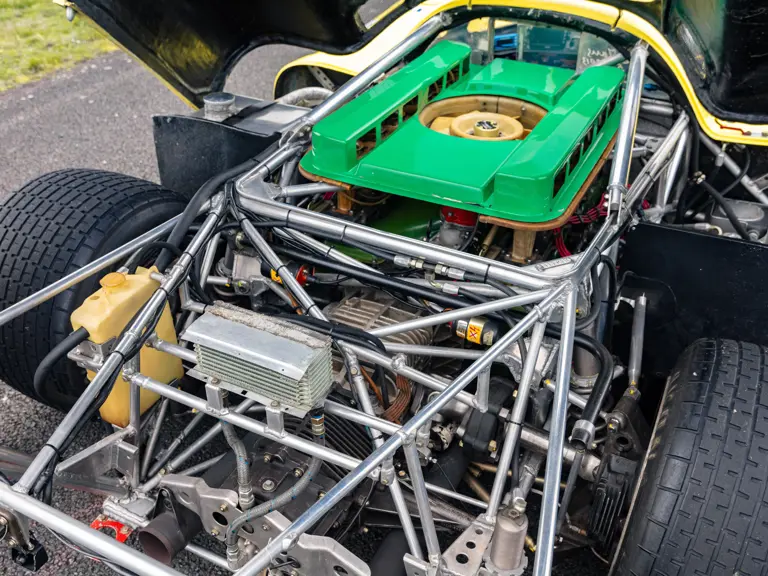

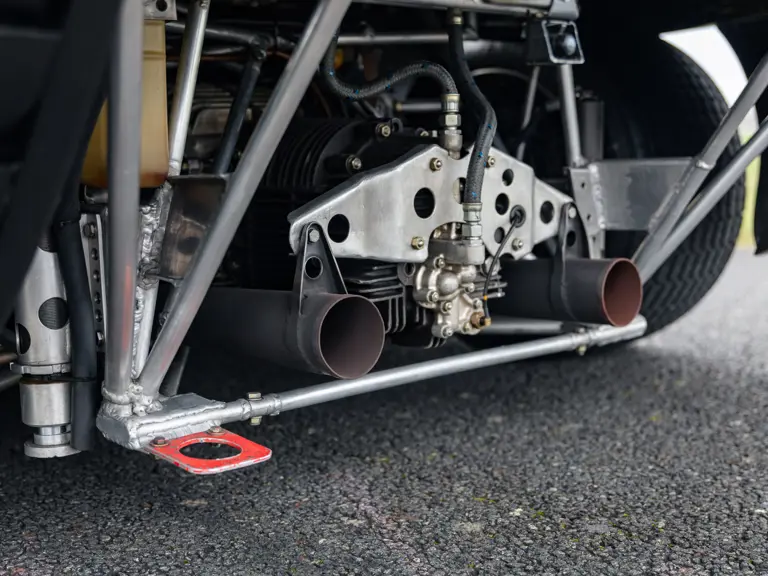

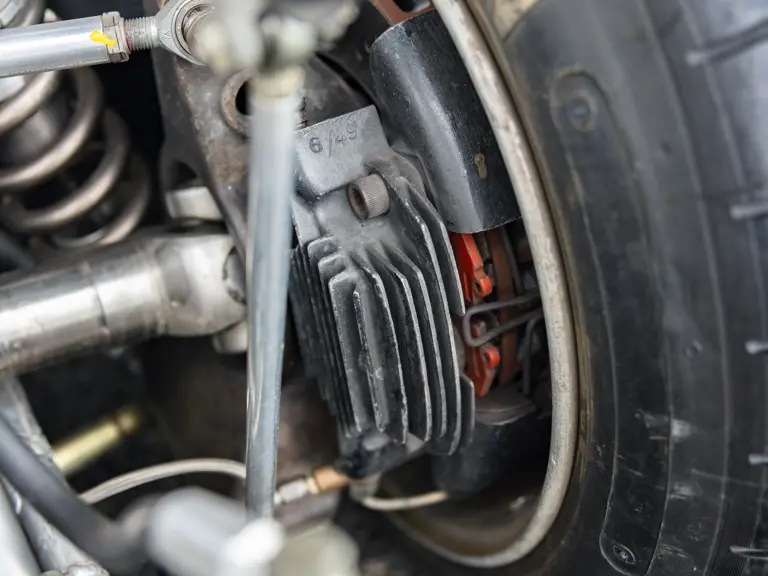

Aided by intimate working knowledge of the 917 and invaluable design support from Porsche headquarters, Kremer set about updating the design to accommodate contemporary tyre construction and aerodynamic practice. Dubbed the 917-K81, the new car featured a Kremer-built aluminium spaceframe chassis similar to that of the original, albeit with additional triangulation and thicker gauge tubing to improve torsional stiffness. In addition, it featured brakes, suspension components and other items of running gear developed on the all-conquering Can-Am programme. The brakes were developed over 1972 and 1973 to meet the requirements of the 917/10 and the 917/30, which weighed in at more than 1,150 kilograms (fully laden) and whose turbo-compressed engines produced up to 1,100 brake horsepower.

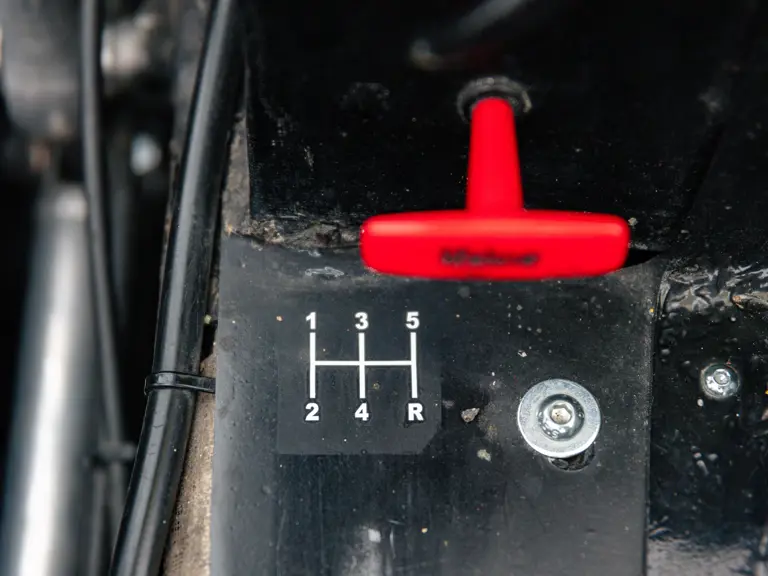

Porsche provided two original Type 912 engines—one of a 4.5-litre capacity, and one of 5.0 litres—to which an original Type 920 five-speed transaxle was mated. Elsewhere, the car’s suspension geometry and bodywork were heavily revised; the latter included the addition of side skirts to enhance ground effect, and a full width rear wing.

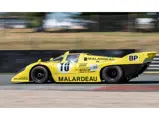

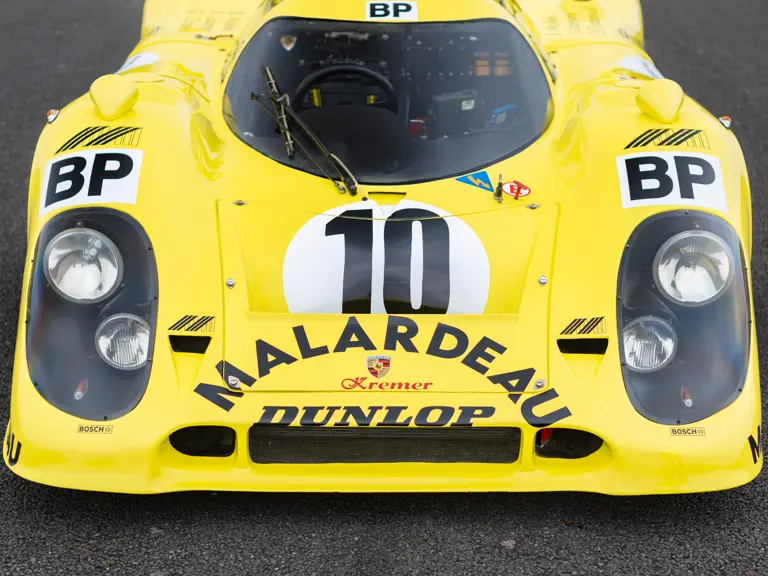

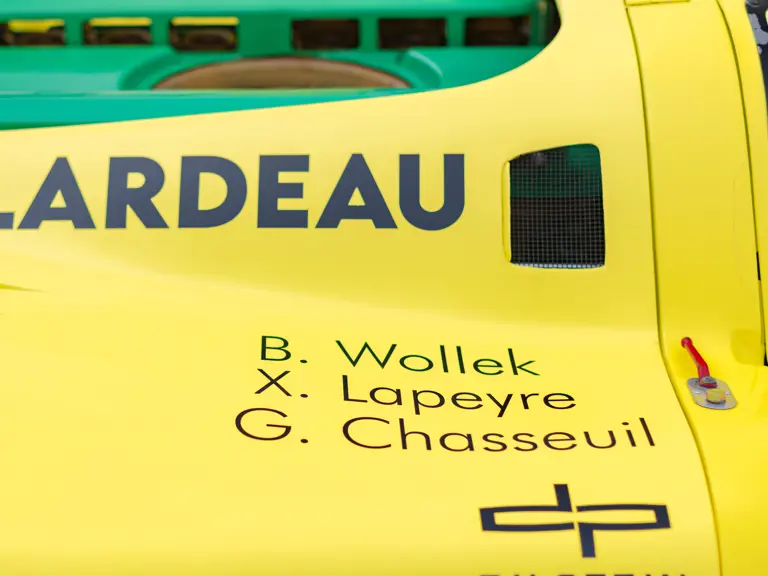

Completed barely a month before Le Mans, the team’s pre-race testing schedule was very limited and critically did not include any meaningful wind tunnel analysis. Nevertheless, Kremer’s entry was greeted enthusiastically by the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, with regular Kremer pilot Bob Wollek nominated as lead driver. Wollek’s fellow countrymen, Guy Chasseuil, and Xavier Lapeyre offered a supporting role, having brought on board welcome sponsorship from BP and French real estate company, Malardeau.

In qualifying, the car proved disappointingly slow on the six kilometre-long Mulsanne Straight—or Hunaudières, as it is known to race-adoring French speakers—due to an excessively short set of gear ratios and prohibitive drag from its oversize rear wing. Eventually, Wollek qualified 18th, albeit 17 seconds per lap slower than the pole-sitting, factory-entered Porsche 936 of Jacky Ickx and Derek Bell, and some 10 seconds adrift of Kremer’s amateur-crewed, sixth-placed 935-K3.

Duly fitted with revised ratios for race day, the car’s top speed was greatly improved. In Wollek’s hands, 917-K81 rose as high as 9th overall, although neither teammate was able to match his pace and the car soon dropped outside the top 20. The team’s plight was further compromised by Chasseuil running out of fuel, while Lapeyre ran wide over a kerb shortly after the seven-hour mark and damaged an oil pipe. Following a significant loss of oil, and resulting damage to the engine, the car was retired in the pits; an ignominious end to the 917’s participation in the event with which it had become synonymous.

Following the appropriate revisions after Le Mans, the car’s second—and final—race outing was at the Brands Hatch 1,000 Kilometres, the final round of the 1981 World Endurance Championship. On this occasion, Wollek was partnered by three-time Le Mans victor Pescarolo—the latter returned to the team for the first time in more than three years. The car immediately proved well-suited to the relatively short and flowing Kent track; its rear wing–in contrast to Le Mans–barely hampering its top speed, and providing enviable levels of grip over the entire four kilometre lap. On this short and snaking circuit, speeds achieved are generally lower than at Le Mans. The 917 K-81 gained excellent cornering aerodynamics, meaning it was no longer penalised by its aero wing at top speeds.

In qualifying, a superb performance by Wollek had the driver eclipsed only by the new Group C Ford C100 of Klaus Ludwig and Manfred Winkelhock, and the 2nd-placed Lola of Guy Edwards and Emilio de Villota. Nevertheless, 3rd place on the grid—just 1.5 seconds off pole—gave the team a much-needed pre-race boost.

At the race start, Wollek eased ahead of the Lola to take 2nd place. The Frenchman shadowed the C100 until a rain shower caused a flurry of pitstops and a reshuffle of the race order. Following the Ford’s retirement on lap 40, Wollek once again found himself in 2nd place, and by lap 43 was challenging Edwards’ Lola for the lead. Once the Briton had pitted, the 917 hit the front, appropriately at the circuit—and in the same event—in which Pedro Rodriguez had given a masterclass in his JW Automotive 917 some 11 years previously. Finally, the 917-K81 was showing its true pace, although sadly this proved only temporary. Wollek retired with suspension failure on lap 52 before Pescarolo even commenced his stint.

The 917 K-81 beat the best time set by a Porsche 917 at Brands Hatch (recorded by Vic Elford and Denny Hulme in April 1970) by almost two seconds, making it the most efficient and fastest Porsche 917 on a technical circuit. Incredibly, Brands Hatch would mark the conclusion of the car’s competitive career. Thereafter, the car remained in Kremer’s possession for several years, prior to its sale to prominent 1960s Porsche 906 and 910 racer Bill Bradley.

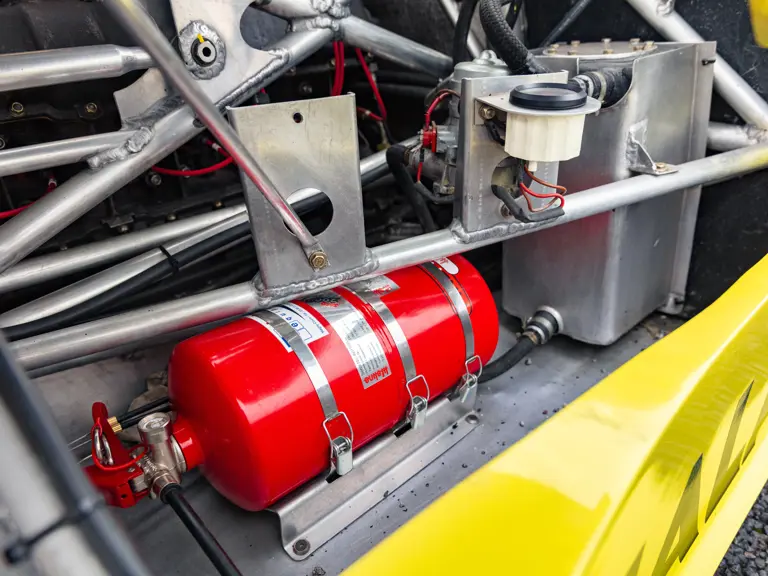

Acquired by the consignor in 2011, the 917-K81 has been maintained by renowned Porsche specialists Crubilé Sport of Gazeran, France, ever since. Its use has been restricted to occasional track days and other non-competitive events, a particular highlight being its participation in the Le Mans Heritage Club Concours at the 2014 Le Mans Classic, for which it received the Special Jury Prize. Furthermore, it has recently benefitted from a complete rebuild of its 5.0-litre engine by Crubilé Sport, the invoices for which remain on file. Upon completion, the unit was statically tested in February 2024; its maximum recorded power representing a significant increase on that achieved by factory-built units in period.

Fastidiously maintained, impeccably presented and representing a fascinating postscript to arguably the greatest of all Porsche Sport Prototypes, 917-K81 would be a highly competitive and exhilarating entry to the many historic racing events for which it is eligible, not to mention a spectacular–and unique–centrepiece for any appropriately discerning competition car collection.

| Monaco, Monaco

| Monaco, Monaco